http://hosted.ap.org/dynamic/stories/U/US_GULF_OIL_SPILL_MARINE_LIFE_FLOL-?SITE=FLPET&SECTION=HOME

June 17, 2010

By JAY REEVES, JOHN FLESHER and TAMARA LUSH

Associated Press Writers

GULF SHORES, Ala. (AP) — Dolphins and sharks are showing up in surprisingly shallow water off Florida beaches, like forest animals fleeing a fire. Mullets, crabs, rays and small fish congregate by the thousands off an Alabama pier. Birds covered in oil are crawling deep into marshes, never to be seen again.

Marine scientists studying the effects of the BP disaster are seeing some strange phenomena.

Fish and other wildlife seem to be fleeing the oil out in the Gulf and clustering in cleaner waters along the coast in a trend that some researchers see as a potentially troubling sign.

The animals’ presence close to shore means their usual habitat is badly polluted, and the crowding could result in mass die-offs as fish run out of oxygen. Also, the animals could easily be devoured by predators.

“A parallel would be: Why are the wildlife running to the edge of a forest on fire? There will be a lot of fish, sharks, turtles trying to get out of this water they detect is not suitable,” said Larry Crowder, a Duke University marine biologist.

The nearly two-month-old spill has created an environmental catastrophe unparalleled in U.S. history as tens of millions of gallons of oil have spewed into the Gulf of Mexico ecosystem. Scientists are seeing some unusual things as they try to understand the effects on thousands of species of marine life.

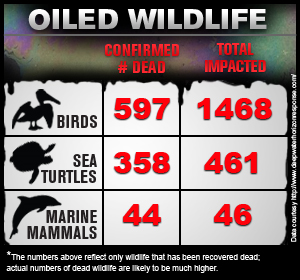

Day by day, scientists in boats tally up dead birds, sea turtles and other animals, but the toll is surprisingly small given the size of the disaster. The latest figures show that 783 birds, 353 turtles and 41 mammals have died – numbers that pale in comparison to what happened after the Exxon Valdez disaster in Alaska in 1989, when 250,000 birds and 2,800 otters are believed to have died.

Researchers say there are several reasons for the relatively small death toll: The vast nature of the spill means scientists are able to locate only a small fraction of the dead animals. Many will never be found after sinking to the bottom of the sea or being scavenged by other marine life. And large numbers of birds are meeting their deaths deep in the Louisiana marshes where they seek refuge from the onslaught of oil.

“That is their understanding of how to protect themselves,” said Doug Zimmer, spokesman for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

For nearly four hours Monday, a three-person crew with Greenpeace cruised past delicate islands and mangrove-dotted inlets in Barataria Bay off southern Louisiana. They saw dolphins by the dozen frolicking in the oily sheen and oil-tinged pelicans feeding their young. But they spotted no dead animals.

“I think part of the reason why we’re not seeing more yet is that the impacts of this crisis are really just beginning,” Greenpeace marine biologist John Hocevar said.

The counting of dead wildlife in the Gulf is more than an academic exercise: The deaths will help determine how much BP pays in damages.

As for the fish, researchers are still trying to determine where exactly they are migrating to understand the full scope of the disaster, and no scientific consensus has emerged about the trend.

Mark Robson, director of the Division of Marine Fisheries Management with Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, said his agency has yet to find any scientific evidence that fish are being adversely affected off his state’s waters. He noted that it is common for fish to flee major changes in their environment, however.

In some areas along the coast, researchers believe fish are swimming closer to shore because the water is cleaner and more abundant in oxygen. Farther out in the Gulf, researchers say, the spill is not only tainting the water with oil but also depleting oxygen levels.

A similar scenario occurs during “dead zone” periods – the time during summer months when oxygen becomes so depleted that fish race toward shore in large numbers. Sometimes, so many fish gather close to the shoreline off Mobile that locals rush to the beach with tubs and nets to reap the harvest.

But this latest shore migration could prove deadly.

First, more oil could eventually wash ashore and overwhelm the fish. They could also become trapped between the slick and the beach, leading to increased competition for oxygen in the water and causing them to die as they run out of air.

“Their ability to avoid it may be limited in the long term, especially if in near-shore refuges they’re crowding in close to shore, and oil continues to come in. At some point they’ll get trapped,” said Crowder, expert in marine ecology and fisheries. “It could lead to die-offs.”

The fish could also fall victim to predators such as sharks and seabirds. Already there have been increased shark sightings in shallow waters along the Gulf Coast.

The migration of fish away from the oil spill can be good news for some coastal residents.

Tom Sabo has been fishing off Panama City, Fla., for years, and he’s never seen the fishing better or the water any clearer than it was last weekend 16 to 20 miles off the coast. His fishing spot was far enough east that it wasn’t affected by the pollution or federal restrictions, and it’s possible that his huge catch of red snapper, grouper, king mackerel and amberjack was a result of fish fleeing the spill.

In Alabama, locals are seeing large schools hanging around piers where fishing has been banned, leading them to believe the fish feel safer now that they are not being disturbed by fishermen.

“We pretty much just got tired of catching fish,” Sabo said. “It was just inordinately easy, and these were strong fish, nothing that was affected by oil. It’s not just me. I had to wait at the cleaning table to clean fish.”

—

Lush contributed from Barataria Bay, La., Flesher from Traverse City, Mich.

special thanks to Larry Lawhorn