University of California Berkeley School of Law | Energy | Oceans | Regulation | Water

Jayni Hein February 4, 2014

As prior blog posts and reports have detailed, hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) has been occurring onshore in California for decades, yet without full disclosure to the public or state regulatory agencies. Recently, new reports of offshore fracking in both California and federal waters have surfaced, showing that fracking has also been underway off the coast for many years, including in California’s most biologically sensitive areas. Yet, the California Coastal Commission, which is tasked with protecting California’s marine environment, was not notified about new fracking activity within its jurisdiction, and issued no coastal development permits to allow it.

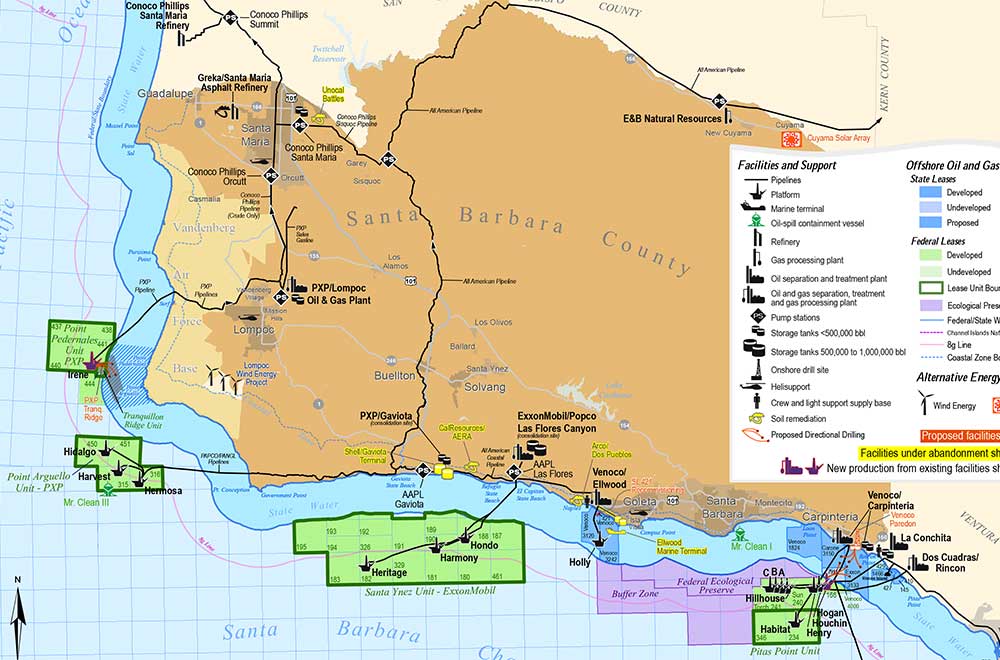

The increased public attention to offshore fracking in the state comes in the wake of a series of stories by the Associated Press in 2013 that revealed at least a dozen offshore fracking operations in the Santa Barbara Channel in federal waters, and additional operations in near- shore waters within California jurisdiction.

Perhaps a reaction to the growing attention to offshore development, last month U.S. EPA, Region 9, announced that it will require oil and gas operators engaged in hydraulic fracturing off the southern California coast to disclose any chemicals discharged into the Pacific Ocean. This disclosure requirement is part of a revised National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) General Permit for offshore oil and gas operations in Southern California.

Risks of Offshore Fracking

Fracking presents risks to the environment, whether on land or offshore. As detailed in our prior Berkeley Law report, fracking

produces hazardous wastewater which must be handled and properly disposed of, poses the risk of well casing failure and spills, and uses precious freshwater resources. Further, fracking injection wells have led to induced seismic events.

Offshore, fracking wastewater is either discharged into the ocean or transported for onshore underground injection. Any well casing failure, spills or blowouts in the ocean will immediately pollute marine waters. Offshore fracking also increases related vessel traffic, with concomitant increases in noise pollution, air pollution, and ship strike mortality for whales and other protected marine mammals.

Much of the recent offshore fracking activity near California has taken place in the Santa Barbara Channel, home to blue, humpback and sperm whales, sea otters, sea turtles, and numerous protected and endangered birds and fish species.

Fracking in California Waters

California, like other states, owns and controls the mineral resources within 3 nautical miles of the coast. The California State Lands Commission halted further leasing of state offshore tracts for new oil and gas development after the disastrous Santa Barbara oil spill in 1969. In 1994, the California legislature codified this ban on new leases of state offshore tracts by passing the California Coastal Sanctuary Act. (See Cal. Pub. Resources Code § 6240, et. seq.).

While California has long had a ban on new drilling offshore, this ban does not prohibit drilling from existing or “grandfathered” platforms in state waters. California’s Department of Oil, Gas & Geothermal Resources (DOGGR), which regulates oil and gas development in the state, has approved individual well drilling plans for at least four such “grandfathered” platforms and five oil and gas producing islands in state waters. And it did so apparently without communicating with the Coastal Commission about this activity. As such, the Coastal Commission never had the opportunity to assess the potential harm to coastal waters from these operations.

The California Coastal Commission has authority to review and potentially prevent the permitting of any activities within state

jurisdiction that may harm the California coast. (See Cal. Pub. Resources Code §§ 30001, 30231). The Coastal Commission is tasked with “protect[ting] the ecological balance of the coastal zone and prevent[ing] its deterioration and destruction.” (Id. § 30001). The Coastal Act requires that the Commission issue a coastal development permit for “any development” in the coastal zone. (Id. § 30600). While the Coastal Commission has delegated most permitting authority to local governments, the Coastal Act specifically requires any development on tidelands, submerged lands, public trust lands, or any major energy facility to obtain a coastal development permit directly from the Coastal Commission. (Id. §§ 30519, 30601).

In evaluating permits, the Commission weighs the environmental impacts of the proposed development against the public benefit, and ensures that the proposed development is consistent with the goals of the Coastal Act. (Id. § 30200, et seq.). And on any public trusts lands, the Coastal Commission, as well as the State Lands Commission, must ensure that any development is consistent with the common law public trust doctrine. (See, e.g., National Audubon Society v. Superior Court (1983) 33 Cal.3d 419, 435-437).

While newly-enacted SB 4 ostensibly applies to both onshore and offshore fracking within the State of California, it does not abrogate the Coastal Commission’s responsibility for protecting the coastal zone. The savings clause in SB 4 eliminates this possibility, and sets DOGGR’s new regulations as a floor, not a ceiling. (See Pub. Res. Code § 3160(n)). At minimum, DOGGR should alert the Coastal Commission to any proposed new or expanded fracking within state waters so that the Commission can exercise its duty to protect the coastal zone.

Fracking in Federal Waters

Three miles off the coast, federal jurisdiction begins and state jurisdiction ends. Here, too, there is a history of long-term bans on new leasing for oil and gas development in federal waters off the California coast, dating back to the Santa Barbara oil spill. But, drilling and production have continued on existing leases, and a limited number of new platforms have been constructed in the area since 1969. The federal Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (“BSEE”), successor agency to the Minerals Management Service (MMS), regulates offshore oil and gas development and exploration.

There are 23 existing oil and gas development platforms in federal waters off the California coast, many of them in the Santa Barbara Channel. Approximately half of the oil platforms in federal waters in the Santa Barbara Channel discharge their wastewater, which often includes fracking chemicals, directly to the ocean, according to a California Coastal Commission report. U.S. EPA has issued a general NPDES permit for offshore oil and gas platforms to discharge this wastewater; however, the Coastal Commission has raised concerns about inadequate monitoring and enforcement of compliance with the NPDES permit terms. (See Coastal Commission Staff Regulatory Report, p. 9).

In federal waters, the Coastal Commission can demand that fracking receives proper scrutiny under the Coastal Zone Management Act (“CZMA”) and object to any consistency certifications if it finds that fracking will pose a threat to the California coast or coastal waters. The Coastal Zone Management Act provides that any federal license or permit for activities affecting the coastal zone of a state may not be granted until a state with an approved Coastal Management Plan concurs that the activities authorized by the permit are consistent with the Plan. In California, the CZMA authority is the Coastal Commission. The Commission has approved consistency determinations on for only 13 of the 23 existing platforms—the rest predate establishment of the consistency review process by the state. However, BSEE has approved applications for permits to drill and applications for permits to modify as “minor revisions” to these platforms, potentially circumventing consistency review under California’s Coastal Management Plan.

Meanwhile, Rep. Lois Capps (D-CA) has called on the federal government to impose a moratorium on fracking in federal waters off the California coast until a comprehensive study is conducted to determine the impacts on the marine environment and public health– much like the statewide environmental study mandated by SB 4. Capps likely faces an uphill battle in the District, as a similar measure was rejected by the House in late 2013.

Coastal Commission Available Actions

Here in California, the Coastal Commission is holding a follow-up meeting next week to discuss the status of its investigation into offshore fracking. The Commission can take some actions now to protect California’s coast and marine waters by:

* Requiring that oil companies fracking in state waters obtain coastal development permits from the Commission before they are allowed to conduct any operations, including expansion of existing platforms or operations;

* Requiring EPA and BSEE to obtain consistency determinations for all offshore oil and gas fracking activities in federal waters off the California Coast; and

* Issuing guidance to local governments to amend local coastal programs to prevent fracking that threatens coastal waters.

There is also much more that the federal government can do to better regulate offshore fracking. This subject is beyond the scope of this blog post, but I flag this for future research and commentary. The Environmental Defense Center in Santa Barbara recently released a report on this topic.

Special thanks to Richard Charter