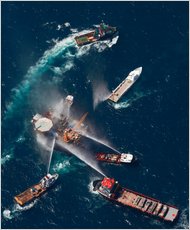

Boats spray water to extinguise the fire aboard the Mariner/NYT

New York Times

September 4, 2010

Blowout Preventer Is Removed

By HENRY FOUNTAIN

BP on Friday removed the damaged blowout preventer from atop the company’s stricken oil well in the Gulf of Mexico in preparation for the final plugging of the well, the government said. Thad W. Allen, the retired Coast Guard admiral who leads the federal response to the spill, said in a statement that the preventer — the roughly 500-ton safety device that failed in the Deepwater Horizon blowout in April — would be brought to the surface on Saturday. It will be replaced by a blowout preventer better able to handle any pressure increases that might result when a relief will is used to pump mud and cement into the well after Labor Day. The damaged blowout preventer will eventually be taken to shore and will be in the custody of investigators looking into the cause of the accident.

_________________________________________

New York Times

September 3, 2010

Spotlight Shifts to Shallow-Water Wells

By CLIFFORD KRAUSS and JOHN M. BRODER

For decades, thousands of oil and gas platforms have operated quietly in the shallower waters of the Gulf of Mexico, largely forgotten by the public and government regulators.

But just as the BP disaster in April brought new scrutiny to the dangers of drilling in the deepest waters of the gulf, Thursday’s fire aboard a platform owned by Mariner Energy could well drag the shallow-water drillers into the spotlight’s glare.

The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation and Enforcement, the new agency responsible for overseeing offshore oil and gas development, said Friday that it was investigating the cause of the Mariner fire, which forced the 13 crew members to jump overboard and rattled nerves in a region that was still coping with the effects of the Deepwater Horizon disaster.

Members of Congress expressed alarm about the accident, with some saying it was proof that drilling laws needed to be tightened. And even industry executives said it was likely the fire would toughen the already difficult regulatory climate for gulf drilling after the Deepwater Horizon explosion killed 11 people and caused the largest maritime oil spill in American history.

“We will use all available resources to find out what happened, how it happened and what enforcement action should be taken if any laws or regulations were violated,” said Michael R. Bromwich, head of the bureau, which replaced the discredited Minerals Management Service after the BP disaster.

Mr. Bromwich has been carefully reviewing shallow-water drilling as he draws up new regulations governing the industry. The agency, which imposed a six-month moratorium on all deepwater projects after the BP accident, has approved only four of 21 new shallow-water drilling applications since it issued new safety and environmental guidelines in late May.

Representative Nick Rahall, Democrat of West Virginia and chairman of the House Natural Resources Committee, said he was “alarmed” by the latest mishap in the gulf and demanded documentation on the Mariner platform from the Interior Department for a committee investigation.

He said the Mariner platform, working in only 340 feet of water, “highlights all too clearly that the risks of offshore drilling are not limited to deep water.”

Although more than 70 percent of all offshore oil production now comes from jumbo oil platforms plumbing the gulf’s deeper waters, thousands of small-scale outfits pump oil from the shallower waters. Currently, 3,333 platforms are drilling in depths of less than 500 feet, compared with just 74 in deeper waters, according to B.O.E.M. data.

The kind of accident that set the Mariner platform ablaze is not unusual. Although the cause is still under investigation, it appears to have started in the crew’s quarters and did not lead to any significant oil leakage.

Under normal circumstances, such an event would have received little attention. There are more than 100 fires a year on oil and gas facilities in the gulf, mostly minor incidents involving welding sparks, grease fires and other mishaps that occur during routine maintenance.

“People need to remember that the environment that people work in offshore is really no different from other industrial plants located onshore,” said Thomas E. Marsh, vice president of operations for ODS-Petrodata, which tracks the offshore industry. “And industrial accidents happen regularly, but not commonly.”

But industry experts say that most accidents happen aboard older platforms that tend to be concentrated in shallow waters.

Mariner operations alone have reported several dozen incidents, including 18 fires, from 2006 to 2009, according to federal records. Although no one died, there were at least three dozen injuries, including one that paralyzed a worker. Several others suffered severe injuries, and some received burns and broken bones. In May 2008, a Mariner rig briefly lost well control and partly evacuated the crew while workers frantically worked to shore up operations.

In addition, since 2006, Mariner Energy has been involved in at least four spills, in which at least 1,357 barrels of chemicals and petroleum flowed into the gulf, according to federal records.

Patrick Cassidy, Mariner’s director of investor relations, said that the company only seriously got into the offshore drilling business in 2006 with its acquisition of properties of the Forest Oil Corporation. “Since Mariner has been operating there, we have steadily improved our performance,” he said. “The performance yesterday is indicative of the improvement. There were no injuries, no spill, and the fire was extinguished.”

Early reports of Thursday’s accident suggested another spill had occurred. But Coast Guard officials said on Friday that only a patch of light rainbow sheen, measuring about 100 yards by 10 yards, had been spotted in morning flights over the area around the platform. The sheen appeared to be residual from the firefighting efforts, the Coast Guard said.

Nevertheless, the Mariner accident has already stoked the intense policy debate over stiffening regulations on shallow-water drillers.

“It will likely provide sufficient political cover for the Obama administration to pursue its current strategy toward stricter offshore regulation,” Robert Johnston of the Eurasia Group, a research and consulting firm, said in a note to clients on Friday. “Even after the formal moratorium is lifted, the pending oil-spill legislation and proposed changes by the Interior Department will translate to higher costs and extended uncertainty for offshore drilling.”

Oil production in the deep slopes and canyons of the Gulf of Mexico surpassed production from shallow waters roughly a decade ago. But for half a century before that, scores of oil and gas companies, big and small, made their fortunes from platforms propped up in waters less than 1,000 feet deep on the inner continental shelf, which can extend for 100 miles or more off the coasts of Texas and Louisiana.

According to data published in July by the Energy Policy Research Foundation in Washington, more than 50,000 wells have been drilled in the gulf’s federally regulated waters since oil production in the area first began in 1947. Only 4,000 of those have been drilled in depths beyond 1,000 feet, and just 700 wells have gone beyond 5,000 feet.

Independent oil and gas companies — far smaller than the majors like Exxon Mobil and BP — represent the dominant shareholders in two-thirds of the 7,521 leases in the gulf, including the vast majority of the production leases in shallow waters.

According to a recent study by IHS Global Insight, the independents produced nearly 500,000 barrels a day of oil last year in shallow gulf waters, while the majors produced just over 20,000 barrels a day there.

But the new accident came at an inopportune time for the oil industry. After BP capped its runaway well and the spill faded from news media coverage, political pressure had grown in the gulf and around Washington to lift the drilling moratorium.

Now, the momentum is likely to shift again.

“This explosion is further proof that offshore drilling is an inherently dangerous practice,” said Senator Frank R. Lautenberg, Democrat of New Jersey, an opponent of offshore oil and gas development.

James W. Noe, senior vice president of Hercules Offshore, the largest shallow-water drilling company in the gulf, said he thought the administration and regulators would use the incident to further slow drilling.

“People that have an agenda that is hostile to offshore drilling will use this incident, there’s no doubt about that,” he said, “But once the facts are understood fully, this will be treated as an industrial accident that could have occurred at a gas station around the corner. It’s just bad timing.”

Andrew W. Lehren and Tom Zeller Jr. contributed reporting.

Special thanks to Richard Charter