http://ocean.si.edu/blog/invisible-loss-impacts-oil-you-do-not-see/

This is exactly what has been bothering me the most about the fact that MOST of the oil never makes it to the surface; we are destroying the very web of life in the Gulf of Mexico. DV

Wed, 06/09/2010 – 9:23am — Chris Mah

Since late April, the world has watched a devastating oil spill from a BP drilling rig spread throughout the Gulf of Mexico and become one of the worst environmental disasters in the history of the United States.

CREDIT: Dr. Allison J. Gong, UC Santa Cruz

We have all seen some of the impacts on large animals: birds, turtles, dolphins, and fishes have all been shown covered in oil with clogged gills, feathers and fins. Undoubtedly, the imagery of these familiar and normally photogenic animals is a powerful, heartbreaking reminder of the damage being done in the Gulf.

But, the effect of the oil on those organisms we do not see may be even more important.

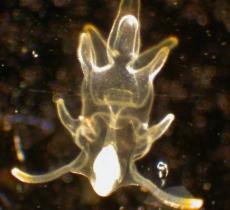

I refer to the invertebrates—animals such as shrimp, crabs, sea stars, sea urchins, clams, snails, and worms, which lack backbones (or vertebrae). These species may not make the headlines as often as larger animals, but they are critically important to the ecosystem in the Gulf. In 1993, Dr. Thomas Suchanek, a researcher at the University or California, Davis published a scientific paper summarizing the effects of oil on invertebrate communities. The paper notes that very low concentrations of oil can produce dramatic changes in invertebrate populations.

Why is this important? Invertebrates comprise the majority of animals in the marine ecosystem. They include jellyfish that live throughout the water column (and are food for turtles and fish); sea stars, which live on the sea bottom; and more importantly the many clams, crabs, shrimps and other commercially important species that are fished in the Gulf. Oil, not to mention the more toxic dispersants being used in the clean-up, can have a wide range of harmful effects, including changes to reproduction, growth, feeding, movement, behavior, and breathing. Destruction of these animals will substantially change the food webs and interrelationships among the organisms that live in the Gulf.

We immediately think about the damage affecting adult animals, but in fact, the more severe damage may be done to those animals we can’t even see—the larvae (baby forms) that live among the plankton.

Seawater is full of plankton—tiny organisms that drift on the currents. Many of these organisms are larvae, or immature animals, mostly invertebrates that grow up to become those jellyfish, crabs, and clams. In many ways, the tiny forms of these animals are the most vulnerable, which is why there are so many of them. In nature, no predator would be able to devour them all, so eventually a significant fraction of those animals grow up into adults. But what happens when you poison the environment where they live? Massive swaths of ocean containing these organisms will likely be obliterated. Some reports are already talking about “dead zones” that could affect species in the Gulf for years to come.

The ecological effects will be even more long lasting. As with the adults, these larvae are part of complex food webs and can play important direct and indirect roles in ecosystems.

The domino effect of wiping out those adults will be devastating not only to the ecology but to the economy. For example, what happens to the shrimp fishery when not only all the adults are poisoned, but the larval forms are wiped out or significantly weakened? The same question applies to almost any edible marine animal in the Gulf of Mexico.

The scope of the damage is sad even if we only see images of poisoned pelicans and other large vertebrates, but what we do not see that may be the most widespread and devastating legacies of the Gulf oil spill.

Editor’s Note: Our guest blogger, Dr. Chris Mah, is an expert in the evolution and biology of sea stars. He works in the Department of Invertebrate Zoology at Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and regularly shares his studies and adventures on the Echinoblog.

Special thanks to Erika Biddle